Coalfield residents living near mountaintop removal mining sites have long suspected this terrible, destructive practice is hurting our health. I first started thinking about it during the long fight to replace the Marsh Fork Elementary School, which sat at the foot of a huge mountaintop removal mining site near my home in Peachtree Hollow.

By Bo Webb / Headquarters Office

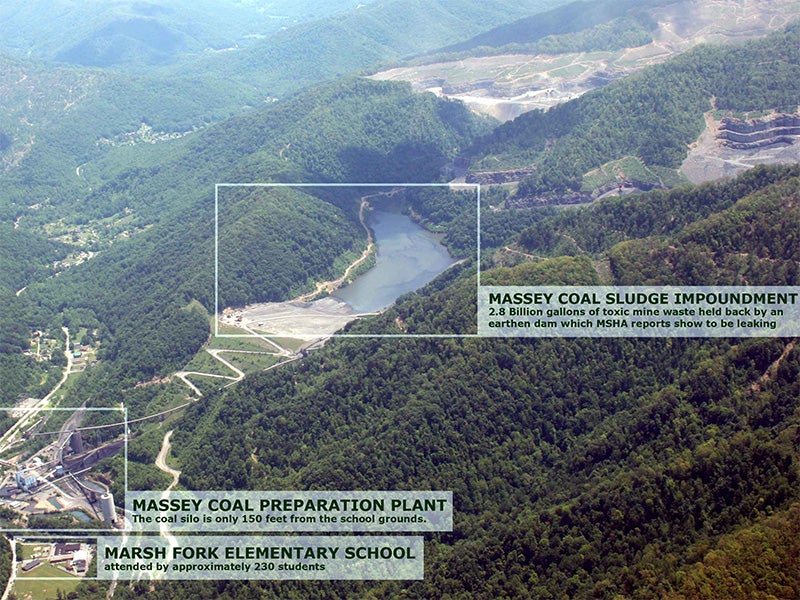

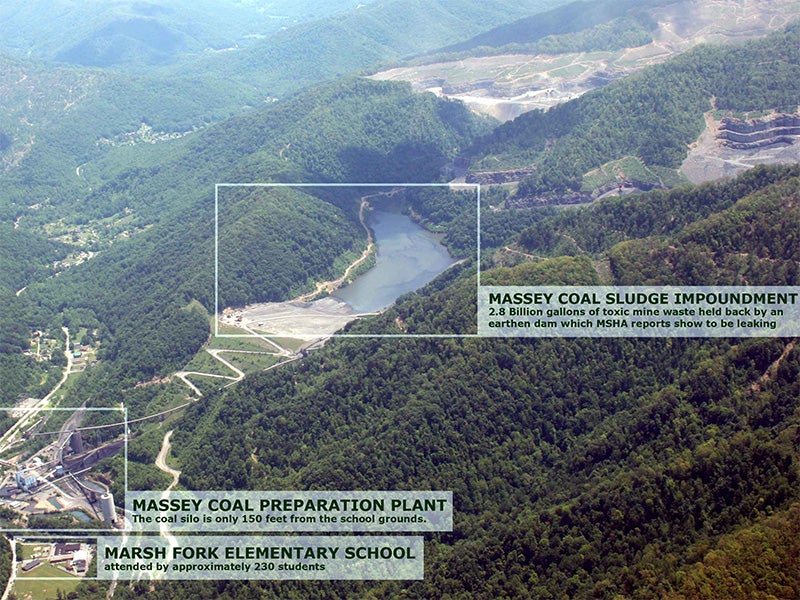

An aerial view of Marsh Fork Elementary School, which sat at the foot of a huge mountaintop removal mining site. (Photo Courtesy of Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition)

This page was published 10 years ago. Find the latest on Earthjustice’s work.

August 27, 2014(Originally published in the Charleston Gazette on Aug. 25, 2014)

Coalfield residents living near mountaintop removal mining sites have long suspected this terrible, destructive practice is hurting our health.

I first started thinking about it during the long fight to replace the Marsh Fork Elementary School, which sat at the foot of a huge mountaintop removal mining site near my home in Peachtree Hollow. We had organized an educational day at the school in 2004, and a teacher came up to me and told me there were a lot of kids at the school getting sick, mostly with respiratory problems.

Coal River Mountain Watch did a survey of 60 families who went to that school and found that 91 percent of the children had respiratory problems. More than 80 percent had felt sick at the school with headaches, nausea and other health problems.

The school was next to a coal processing plant and below a huge sludge impoundment, and in large part surrounded by massive mountaintop removal mining sites.

It got me thinking about how many people I knew who were sick and dying of cancer. Cousins, neighbors. My good friend Judy Bonds had cancer. (Bonds died in 2011.)

Dr. Michael Hendryx at WVU had started doing some research. It wasn’t 100 percent conclusive, but all indications were that a lot of people who lived near mountaintop removal sites were getting sick and dying. Other research showed the rate of birth defects was increasing dramatically in regions where mountaintop removal mining was becoming more prevalent.

We worked with Dr. Hendryx to design and conduct a study that found cancer rates among residents near mountaintop removal mining sites are twice those of West Virginians in non-mining areas, and nearly triple the national average.

These were peer-reviewed, scientific studies, and year after year, the evidence grew. We were fighting mountaintop removal mining permits in the courts, based on violations of the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act, and it just dawned on me that we needed to do more. People were sick and dying. This had to stop.

Several of us got together and formed the Appalachian Community Health Emergency Campaign. We worked with our partners at Earthjustice to draft the Appalachian Community Health Emergency Act (ACHE Act).

The ACHE Act is an elegant bill. It establishes a moratorium on new mountaintop removal mining permits while the director of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences initiates comprehensive studies into the health effects of the mining on people in surrounding communities.

While the studies are ongoing, the legislation requires monitoring of air, water and noise pollution from existing mining locations.

A small, one-time fee on mining companies will pay for the studies and the monitoring.

Once the studies are complete, the U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary will be directed to publish a determination of whether mountaintop removal mining is causing health risks to nearby communities.

The moratorium on new permits will continue unless the secretary determines there is no health risk.

The ACHE Act was introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives on Feb. 6, 2013, by U.S. Rep. John Yarmuth (D-Ky). It currently has 47 co-sponsors.

This is personal to me. In 2012, my wife Joanne was diagnosed with lung cancer. She passed away three months later. It was devastating. We had been married for nearly 40 years.

All around us, people are getting sick. They’re dying. And the scientific evidence tells us mountaintop removal mining is the cause of much of this suffering.

We have a bill that would really end this. I think we can do it.

We have to do it.

Take action to tell your member of Congress to support the ACHE Act. And learn more and find other ways to support the ACHE Act and ACHE Campaign.

Earthjustice originally featured Bo Webb as a Mountain Hero in 2011. A sixth-generation resident of the Coal River Valley, West Virginia, Bo is a co-founder of the ACHE Campaign to get the Appalachian Community Health Emergency (ACHE) Act passed by Congress. The ACHE Act is the first law ever proposed that would end the human rights and human health disaster that is mountaintop removal in Appalachia. Earthjustice has partnered with the ACHE Campaign to educate members of Congress on this problem and work for passage of the ACHE Act.

Bo is a former board president and current member of Coal River Mountain Watch. Bo, a Vietnam War veteran, was one of the community members who helped move Marsh Fork Elementary School out from under a 2.8 billion gallon sludge dam. In 2010 he was one of the leaders of the largest ever national protest on mountaintop removal mining, called Appalachia Rising, in front of the White House, and was co-founder of Mountain Justice Summer.

For his tireless advocacy, he was awarded the Purpose Prize in 2010.